Ways of seeing in the age of brainrot.

On gazing well and the role of art in the age of (nonsensical) visual clutter.

I’ve been encountering a deeply uncomfortable feeling on social media lately, particularly when I accidentally consume what’s now being called brainrot content. I’m sure you can relate to this as it honestly takes me a while to remove the nonsense flavour of such visuals from my head. Brainrot, a colloquial term for overstimulated, nihilistic digital content (most of them being AI generated eg: Italian brainrot) has become a collective condition, both a joke and a diagnosis. Navigating the sea of content is tricky because you never know when something useless will suddenly hit you. Algorithmic curation on social media is unintentional at best, indifferent at worst. Virality metrics alone now decide what’s visible and what isn’t. Perception has become machine-mediated, triggering a domino effect on how we move through the world outside the digital space. The individual gradually loses agency over their own capacity for sight and experience, subtly mediated instead by algorithmic worldviews we never subscribed to.

Brainrot is a symptom of a world growing tired of itself, tired of meaning, tired of coherence. Like a diseased limb in the cultural body, it festers. Some researchers now warn that this onslaught of brainrot imagery correlates with measurable reductions in grey matter. So how do we go about designing our perceptions and reclaiming agency from these algorithm-induced visual loops?

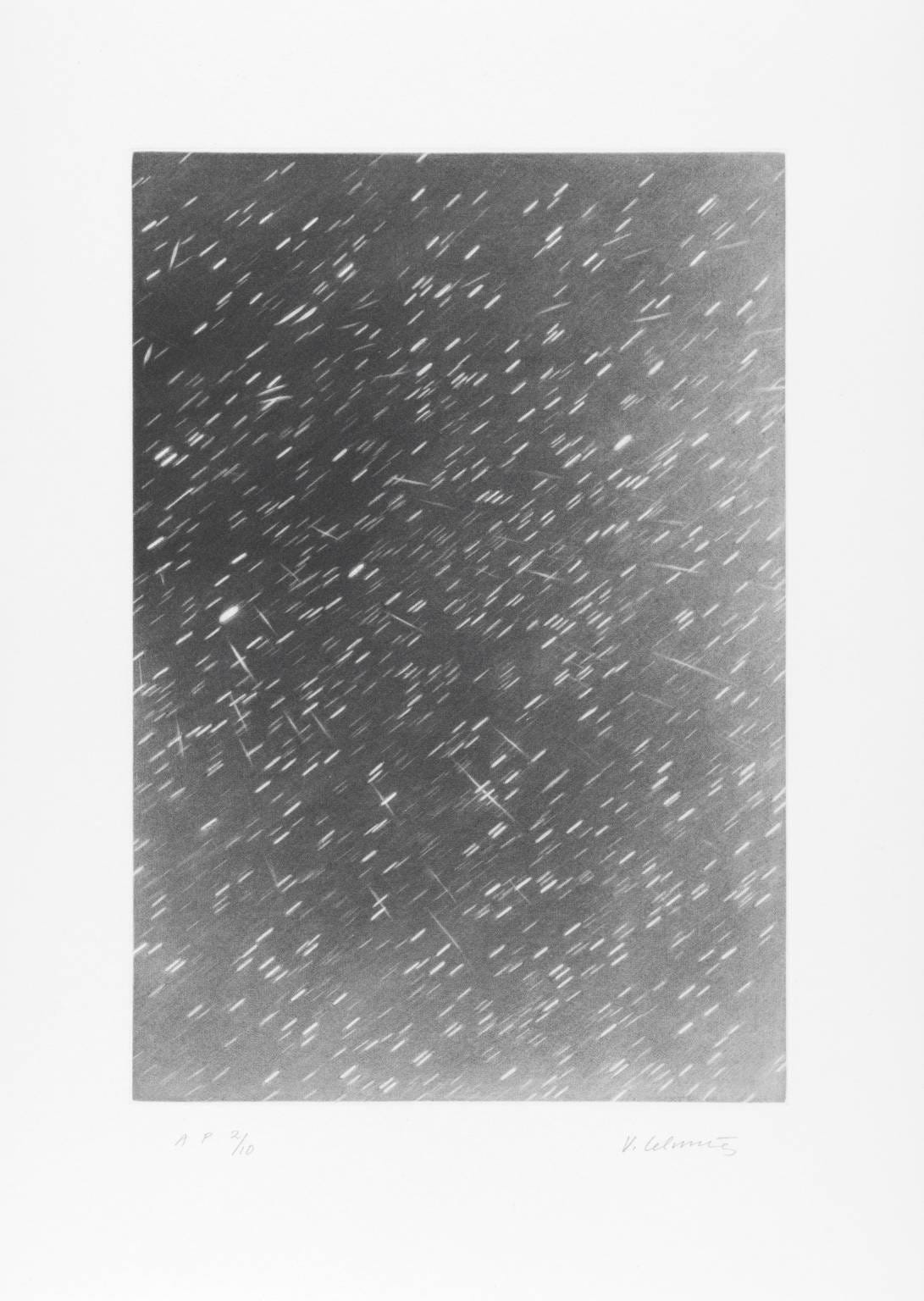

What does an image mean in the age of AI-driven content? As a painter, my practice necessitates to produce an image slowly, intentionally. A photographer captures one through composition, timing, and intuition. A careful examination of time and space is done, a creative resolution is arrived at and an image is brought to life. It’s a kind of birthing and mothering that is sacred in every artist’s practice. When brought in the curated context of exhibitions and community programmes, the consumption of that image too is intentional, spacious. Viewership is softer and transformative. In the age of brainrot, anything and everything is produced and consumed at once with frazzled attention spans. Another important thing for me is that image-making begins with the awareness that nothing exists, that a relationship to emptiness or no-thingness behind the eyes must first be established. That emptiness is the necessary foundation for any worthwhile image. In technological modernism, where AI seems to have replaced the need for creative faith, images layer endlessly upon each other, generating a kind of mythological sludge. Crude, nihilistic humour has become the flavour of the youth, and from this tone, entire media ecosystems and behaviours are now shaped. I won’t deny the fact that the lure of cursed images speaks to the darker regions of our subconcious patterns. But at what cost? How is it, in any way, supporting our evolution?

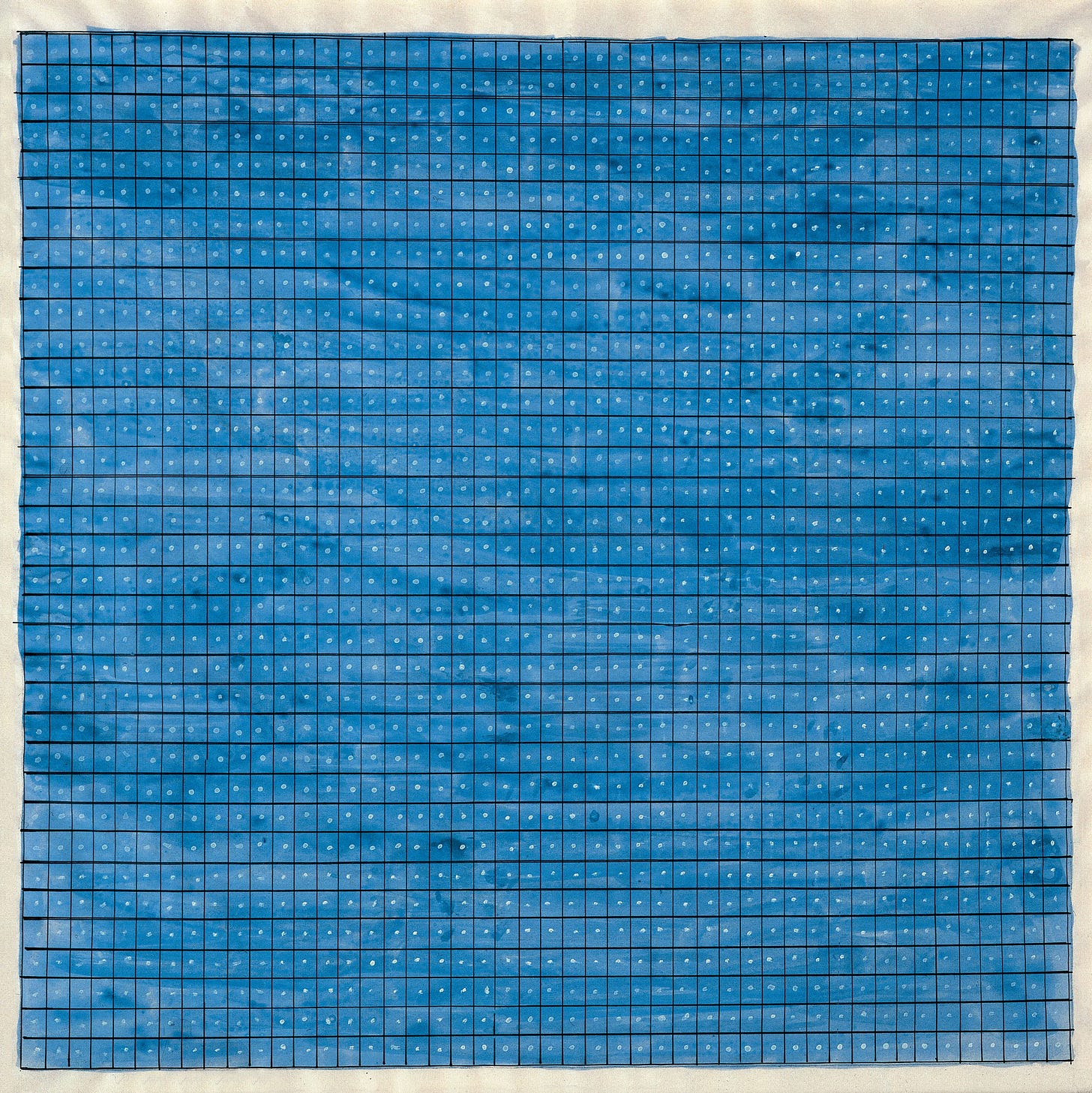

In Vedantic philosophy, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras speak of drishti, the point of gaze, and the vital need to steady the senses in order to perceive with clarity. The sutras emphasize the cultivation of pratyahara, the withdrawal of the senses from external distractions, as a prerequisite for inner stillness. Sight, in this context, is an active, disciplined engagement, a yogic practice of returning again and again to the Seer (drashta), the unchanging witness within. For advanced practitioners, mastery over the movement of the eyes, over what and how we look, is a method of softening the mind’s fluctuations and tempering its restless urges. To see clearly is to still the waves of the mind (chitta vritti nirodhah). In Tantra, practitioners make geometric drawings or Yantras to meditate upon. The drawing could be considered as a form of sentient technology in itself as it is believed to be activated by the qualities of specific deities of aspects of higher conciousness. Simply gazing at a yantra can drop the practitioner into a state of equanimity.

In Islamic Sufi practice, muraqaba (from the root raqaba, meaning "to watch or observe") is a form of deep meditative attention where the practitioner enters a state of watchfulness of the self, the breath, and ultimately, the Divine. It is often described as placing the heart before God, and training oneself to become conscious of divine presence at all times. Unlike Western notions of concentration, muraqaba is a soft, spacious kind of attention. It involves visualizing divine names, entering states of silent contemplation, or imagining the heart as a mirror being polished until it reflects Truth. The gaze here is internal, yet transforms one’s external perception. In this light, the Sufi tradition invites the idea that what we perceive is shaped by the purity of our internal vision. A distracted mind sees distortion; a clarified heart sees Reality as is.

This doesn’t mean we make ourselves averse to discomforting images or protect our sight at all times, because that’s simply not possible. Nor is it easy (though not impossible) to master the sense of sight like an advanced yogi, especially when our lives are so relentlessly demanding. But perhaps we can practice, even for a few moments daily, detaching ourselves from the emotional consequence of sticky visual experiences. Can we retain a part of ourselves from being pulled into the sinkhole of overstimulation? Can we learn to tune in deeply to our sight, to pay attention to our attentiveness?

In our contemporary flood of images, ancient practices are an urgent antidote. Without a calm mind and refined attention, the endless scroll of imagery fractures our perception. Each uncurated image adds to the static of internal chatter. But what if our gaze could be trained like a muscle? In this sense, curation becomes a necessity than just a segmented activity gatekept by the cultural industry, a spiritual and cognitive hygiene, a daily practice everyone must engage in to preserve mental clarity. Curating our gaze is curating our consciousness. We need to remember that to look is itself an art form in a visually splintered culture.

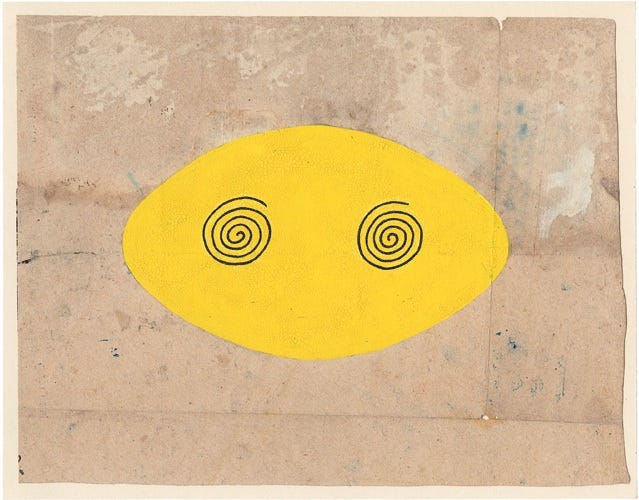

The modern lore of brainrot reduces images to mentally fatiguing memes and somewhere, the human drive for seeking meaning is lost. So where does art stand among this noise? When imagery is cheapened and perception hijacked, art remains one of the last domains where slowness and aesthetic care still matter. It invites attentiveness. A good artwork doesn’t demand a scroll or swipe, it asks you to stay with it, all the while stretching our experience of time to the breadth of our attentiveness. Art expands our limitations of visioning, of visualising. It reminds me of the aliveness of my own seeing, giving its momentum a visible shape. I gaze, and in my gazing I realise something about myself. It hones my ability to sense and revel in nuance. All because art, when presented spaciously, invites a new relationship to time, one that feels richer than mere survival.

Art gives us choice. This runs counter to brainrot culture, which thrives on hyper-speed consumption and visual numbness. I think that culture makers of today hold a great responsibility for social well-being. But this doesn’t have to be carried by those in that industry alone. Curating our lives, as overused as the phrase sounds, can be approached as a simple daily practice of stewarding our visual inputs. As a protocol, choose to practice 5 or 10 minutes of ‘slow looking’ at images that invite your sense of wonder. I promise you, it can be incredibly healing and energising for your creativity. I often curate a moodboard of joyous and meaningful images that support my worldviews and art practice. It helps me remember, every day, how I want my life to look and feel.

So, which image are you choosing today to re-train your gaze?

xo