Re-enchanting Architecture (Part 1)

How can 'soft architecture' reimagine our disembodied relationships with(in) space?

Architecture, if perceieved as a mediator, allows a form of social dreaming through the organization of space—and, by extension, time. My recent interest in this doesn’t stem from a single moment or revelation, but an underlying current of frustration. Living in a city like Mumbai, I am struck by the excess and parasitic wastefulness that dominate its material landscape, as if this messy, disorgansied indulgence (or lack thereof) is the theme of our collective timeline. How we experience space and environments often feels deeply unconsidered, treated as an afterthought rather than a living dialogue between design and its inhabitants.

In my spiritual practice, we recognize the environment as the ‘first body’. When the spaces around us are ill-considered, they imprint themselves on our flesh-bound bodies, mirroring their neglect. This conflicted connection between the outer and inner worlds feels urgent to address, as architecture—more than any other discipline—through its mediative (and meditative) capacity has the potential to heal or harm us on both a societal and personal level.

Soft architecture is a proposition that rejects the mechanistic demarcation of space into sterile compartments of efficiency, while also challenging the rigidity of such infrastructures that narrow our perceptions of space, time, and community. Instead, it offers blurred circumferences of movement and an escape into states of environmental and bodily confluence, prioritizing social well-being. Considering skin as the first point of contact to spatial intimacy, what forms of embodiment can architecture revolutionize in a contemporary world where digital infrastructures dominate for our attention? How can spatial design foster porosity, inviting us back into our bodies and breath rather than encouraging an endless escape from our place in time?

This recalibration of body and space is not an isolated theory. Artists and architects have long been exploring new frameworks that embrace soft, fluid and lightweight alternatives —whether through bubbletecture, pneumatic structures, or nomadic designs. These approaches reimagine architecture as a gateway into material intimacy and agency.

Pneumatic and Inflatable Structures

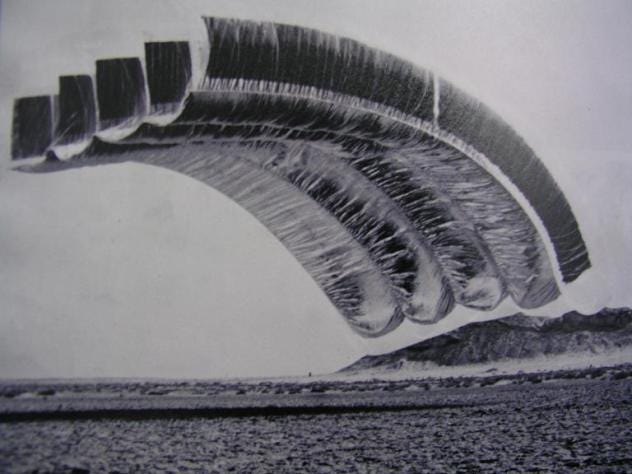

Pneumatic structures harness the potential of air compressed within flexible membranes to create progressive and lightweight alternatives to ‘normal’ construction methods1. First posited in the 1940s by the engineer Walter Bird, artists such as Graham Stevens were quick to pick up this revolutionary idea and embed them into artistic contexts to reimagine social + spatial configurations. Graham pioneered the ‘participatory inflatables’- dynamic structures that shape the interactions between human and environment.

Even though the rigorous practice of pneumatic architecture faded in the 1970s, contemporary artists have continued to explore its potential in shaping the "urban ecologies" of the future. Among these explorations, one that strikes me the most is Tomas Saraceno’s Cloud Cities (2011), described as “an aerial exploration of the entanglement between human beings and their environment in its entirety as a move toward a mental, social and environmental ecology.”

Saraceno's work reimagines the cloud as a metaphorical structure—cellular flying cities and imaginary floating gardens—challenging the entrenched meanings of territory, as well as the national, racial, and political boundaries of modern urban societies. In doing so, this installation proposes a utopian theory of ‘boundlessness architecture’2.

The visionary utopianism of Cloud Cities reflects a new approach to social engagement using resilient and softer structures, drawing from a lineage of architectural dreams like Archigram’s Walking City and Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes.

Nomadic and Wearable Spaces

Lucy Orta’s Refugee Wear project (1992–2007) presents prototypes of modular shelters that transform into clothing and transport bags, offering safe, mobile refuge for individuals navigating human distress or unsuitable social environments. This project serves as a compelling speculative experiment, addressing both immediate and future scenarios.

While its subtle aestheticization may cater to the contemporary art and theory discourse, Refugee Wear maintains a solution focused stance, offering an essential functional critique at the intersection of architecture and fashion, highlighting its potential to protect and sustain life in precarious conditions marked by violence and displacement.

Biomorphic subversions

Biomorphic subversion in architecture nurtures embodied resonance by embracing other-than-human aesthetics, even inviting non-human entities as co-creators of space.

Neri Oxman’s Silk Pavilion (2013) is a striking example of biomimicry as well as utilising the abundant and intelligent resources of nature in architecture, pushing the boundaries of materiality and construction by collaborating with our insect companions—silkworms in this case. By combining computational design with biological processes, the pavilion proposes methods “that unite the biologically spun and the robotically woven.” This project reimagines the role of living organisms in the design process, not as tools but as co-creators.

What resonates deeply with me is how this project subverts the violent complexities of traditional sericulture practices, which often exploit silkworms for silk production. Instead, Oxman’s approach places silkworms as active participants and collaborators in the creation of habitable structures. Are multispecies collaborations the future of construction? Neri is a pioneer in provoking this idea to reimagine urban spaces beyond its systemic organisations. The overturning of specist heirarchy in favour of new models of ‘crafted’ construction is an invitation to softness that we all need.

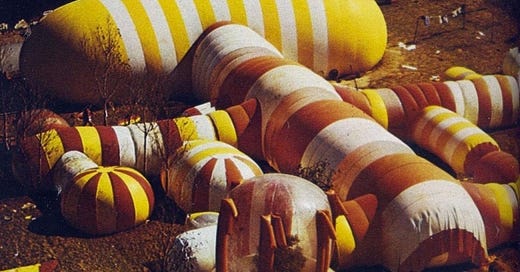

One of my favorite artists, Ernesto Neto, uses the biomorphic approach in his installations to profoundly shift the spatial perception of his audience. For me, he is a champion of soft spatial design. His use of mesh-like polyamide fabric and soft, bulbous silhouettes—forms that irresistibly invite touch—creates what can best be described as a ‘holobiontic’ quality, where human interaction and space merge in an dynamic, symbiotic relationship.

Neto activates a liquid-like animality in space, reshaping our sense of embodiment through tactile and sensuous materiality. Space is transformed into a enlivened, elastic material, a pulsating underbelly of something gianormous and soft—caressable, and permeable. There is a great sense of humor and romance radiating in his work, teasing out our desensitization due to the rigidity of ‘concretized’ architecture and illuminating a delicate, porous quality that jolts the body’s sensory capacities in all the right ways. The anti-concrete motivation behind his work animates his interventions with a womb-like aliveness, echoing the ethos of the ‘carrier bag.’ Neto’s biomorphic structures bridge a primitive approach to the practice of ‘sheltering’ with a futuristic drive for aesthetic languages that transcend mechanistic ideals.

Soft architecture, under Neto’s context, reveals a vital realization: the need for accessibility and agency over our sensory experiences. Neto mentions in an interview that his work is really about time, ‘having the time to breathe and think’3. Modern architecture, driven by cost-saving pragmatism and rapid output, often produces repetitive frameworks that dull our biological sensitivity. The mass concretization of cities like Mumbai has created a looming collective energy of ‘spatial dysmorphia,’ leaving us disconnected from the spaces we inhabit, and inevitably leading to a depleted relationship with time itself.

Soft architecture allows embodiment at multiple scales— from the macro to the micro. It means recognising the mutuality between the agency of space and placing equal value on human and other-than-human stakeholders in spatial narratives. While I don’t expect new architectural projects to emulate inflatability for mass production, nor can we realistically employ silkworms to build residential complexes at scale, I care deeply about how these concepts can influence the way we think about designing spaces for our communities. These experiments, though speculative, offer blueprints to reconsider how we prioritize materiality, collaboration, and sensorial engagement in architecture. And this would really mean renegotiating with our ‘always-been-this-way’ approach to space and habitation.

x

(Stay tuned for part 2 <3)